This was a book that spoke to me on a lot of personal levels, and helped to make a lot of sense of who I am and who I’ve become as a result of the experiences I’ve had in my life, namely my time serving in the U.S. Army. Sebastian Junger, a highly regarded combat journalist and writer of several other works, gives a detailed and well-supported argument in his book, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging for what he sees as a general and significant disconnect in the modern American society from the earlier tribal roots of the human species. This disconnect, Junger suggests, may be a leading and significant root cause of many of our modern ailments and psychological afflictions. The idea being that we are simply not living as our ancestors lived, physically, emotionally, communally or psychologically.

Early in the book, Junger discussed statistics and studies that arose during the early American settlement and associated wars with the indigenous inhabitants of what would eventually, and bloodily, become the United States of America. One of the more unexpected and difficult dynamics of these conflicts and the clashing of modern Western European culture with the stone age tribal cultures of the indigenous peoples was the thousands of white European Americans who allegedly defected from advanced society and joined the tribal clans of Native Americans. Some of these defections came in the form of captured men, women and children who, by the time they found themselves in a situation to return to white society, no longer wished to. What Junger does not discuss is the potential role in these cases that Stockholm Syndrome could have taken in preventing these people from wanting to return to modern life, and certainly a child who was captured or born in captivity would have a much easier time adopting the culture of its captors and therefore less apt to assimilate back into white society. I would think this could have played a significant role in the phenomenon.

Nevertheless, there were a significant number of cases of voluntary defection of people with European ancestry simply walking away from the budding urban and industrial life and finding a home with the tribes of North America. It’s suggested by Junger that this was simply a calling home of people who had an evolutionary trigger activated and, no matter how long back in their ancestry it had been since their forefathers wore buckskin and howled at the moon, the lure of a return to savage life, once it became possible to do so in the New World, was too strong to ignore.

The tribal life, although demonstrably dirtier, more dangerous and arguably harder to endure, offered many things that modern life had left behind. The sense of community and group survival was rapidly disappearing in modern society and replacing it was a highly individualized and competitive culture. Tribes competed, often violently, but they competed almost exclusively with each other and rarely ever was there competition to the point of in-fighting within the tribe. Liberty, especially that of women, was much more valued in the indigenous tribes. The women were free to marry whom they wanted and to cease being married whenever they chose. All members of the tribe had specific tasks and chores to accomplish for the greater good of the community, but the hierarchies were small and simple. Class and status was not celebrated and the tribal way of life made it nearly impossible for any one tribe member to amass a disproportionate amount of wealth above the rest of the tribe that could be passed down to offspring who did not earn it. Leadership existed and warriors celebrated, but all in all every member of the tribe acted in the interest of the tribe. This snapshot of prehistoric culture found in the American wilderness, and eventually hunted down to near extinction, represented a more natural and enduring culture than what the westward expansion and Industrial Revolution was affording the emerging American lifestyle.

Junger spends some time contrasting the historical tribal culture with the modern American one in ways that made a lot of sense to me. Like all things deemed progressive, the second, third and beyond order effects of the rapid rate of societal evolution was not immediately clear, and is only starting to become understood today. Our natural environment is being decimated, our population is increasingly unhealthy (despite all the modern marvels of medical science), wealth inequality is growing (as our Chief’s no longer have to answer to their tribe only their shareholders), our sense of community has been diminished to the point of forming home owner’s associations to compel our neighbors to cut their lawn so we don’t have to risk actually talking to them. Most pointedly in this book, our psychological states have become increasingly troublesome. Despite all the comforts of modern life, we are anxious, we are depressed and we are suicidal on higher scales than previously known in western culture. It’s difficult to get a handle on what the suicide and depression situations were in tribal cultures as such things were not well studied in the North American Natives. In general, suicide in a tribal culture came when one was no longer of any use to the tribe.

Old age beyond ability to do one’s fair share of work, dishonor on the battlefield and significant physical disfigurement were some reasons known to lead tribe members to take their own life. Although emotional parallels can be drawn between the feeling of exile and ability to contribute among tribal and modern urban cases of suicide, the tribal reasoning seems to be tied to physical impairment rather than irreconcilable emotional states without clear physical motivators. It would seem that some of us are simply having a tough time accepting the rapidly changing and continually less agrarian and community oriented lifestyle that is evolving around us.

To discuss and study the stark differences between these two worlds, the tribal and the modern civilized, it is natural to look at a group of people who have significant experiences living in, and traveling back and forth between, the two worlds. That group is combat veterans. This is where the book really begins to hit home and speak to my personal experiences and some of the emotional and cognitive states I have found myself in both during and after my time in the military.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the modern scourge of the military veteran. Although the actual loss of life and overall viciousness of combat operations as compared to our earlier wars has diminished greatly, we find ourselves with an increasing amount of diagnosed psychological impairment in our military members. To be clear, I am not someone who feels they have been psychologically impaired by their military service. If anything, I would describe my psychological state following military service and deployment as Post Traumatic Growth, which is the less notorious phenomenon of experiencing increased cognitive and emotional ability following a period of extreme stress and feeling of danger. Regardless, what Junger goes on to describe felt very familiar and reminiscent of several key crossroads I have come to in my post military years.

One of the strange parts of the emergence of the PTSD culture is that, as previously stated, by most objective and subjective measures, war has gotten a lot nicer in the modern age than it was in our grandparent’s time. Our loss of life and limb is down, the number of soldiers who actually see a fire fight is low, the carnage and mayhem of world wars fought in bloody trenches is something that is simply not seen today by the average American service member. Yet, there does seem to be a greater psychological toll that is occurring. One of the reasons Junger hypothesizes this could be is simply a cultural shift that has gone towards providing a victim mentality to those who have experienced traumatic events. The tendency is to take a veteran who is struggling to re-introduce to civilian life and hand them a diagnosis and disability check for the rest of their life. Junger cites statistics that show many veterans seek treatment and go to appointments long enough to be given a 100 percent disability classification (meaning they will receive a tax free salary for the remainder of their life) and then promptly cease seeking treatment once they have done the bare minimum needed to receive the lifetime salary. What Junger suggests is, in part, we are not practicing good diagnostic and treatment standards and there is significant abuse of the system. It is apparently not uncommon for these abuses to be noticed in therapy groups and VA medical centers and often scuffles between the truly needy and the abusers have to be quelled by the staff.

Although these abuses are certain to exist, it’s impossible to say to what significance they play a role in the increasing psychological cost of war, and systemic abuse is not the main point of this book. The main point in this book that Junger seems to be making is it’s not the war zone that causes psychological problems in many returning veterans. Instead, it’s the world they return to. The combat zone isn’t the problem, the modern world of competitive individualism and victim mentality, where no one knows their neighbors and no one regularly sees or works with the members of their social networks, and fewer and fewer people take responsibility for their actions or their situation in life is the problem. American veterans return to a society that habitually thanks them for their service, which can only emotionally serve as a reminder that only the very few will ever serve, while the rest just go about their lives. Junger cites the mandatory military service culture in Israel as supportive of this dynamic. Nearly half of Israel’s citizens serve in the military in some form at some point in their life, so Israelis walking around thanking each other for their service would be as natural as Americans walking around thanking each other for paying taxes. We might all have different feelings about what it means to pay taxes, but it’s nevertheless something that most of us do. It’s simply the norm.

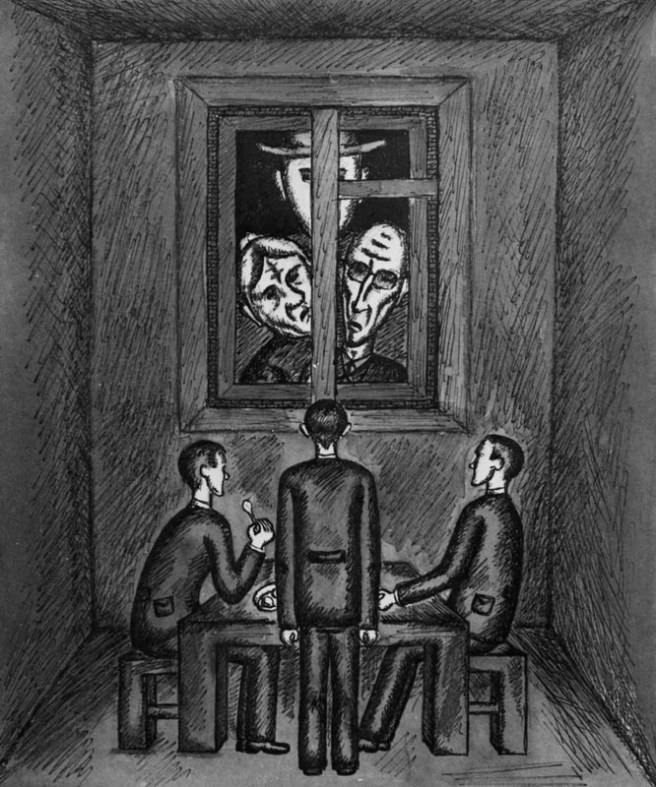

The Israel contrast goes on in this book to point out something else modern American life has lost in relation to primitive tribal cultures; in the primitive tribal culture of North America (as well as the modern tribal culture of Israel), the community existed extremely close to the tribe’s conflicts. Warriors were the direct defenders of the society, and the enemy was not simply an abstract idea that came through the TV screen from the other side of the world. The enemy was there, lurking in the shadows, planning to strike at any moment. While I’m certainly in no hurry to live somewhere where I feel constantly threatened by invading forces, I have to admit that doing so provides a catalyst for a group of people to forget their differences and bond together for a common cause. The terrorist attacks of 9-11 serve as support for this, when America found a level of unity and patriotism not experienced for many decades prior, and has asymptotically diminished since.

Given this context, I can say from experience the military is a very tribal culture. Through training and environment, the differences that soldiers may have; be them racial, religious, gender, political and during my time in the army even sexual preference differences, become not as strong of focal points for soldiers. My time in the army was still underneath the don’t ask, don’t tell policy towards sexual preference, but for younger lower enlisted and officer classes it was generally well known who was and was not gay. Even the few who may have not liked homosexuality where not very apt to report their fellow soldiers for behavior they disagreed with. The camaraderie and tribal dynamics tended to govern in these situations, and only the old timers really expressed any concern for the sexual preferences of others.

For those who had families, the family too was a part of the tribal culture. The family dealt with deployments and field training issues in their own way. There were support groups and community advocacy groups, children went to school and associated with other children of military parents and a commander’s spouse often acted in several key roles within the community. The extended tribe was an important part of the success and motivation for the warrior members of the tribe.

During deployments, the tribal mindset increases. It’s often been said that soldiers don’t really fight for their country when they are in a war zone, they fight for the men and women who are directly around them; their tribe. I think there is a lot of truth to that. There is a phrase that Junger uses in this book that I have seen used in others as well to name the mental shift that occurs in solders who are deployed to combat zones. That phrase is the hive switch. In his book The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt suggests that human beings are 90 percent chimpanzee and 10 percent bee. He describes the hive switch as a mental state that a human enters (notably in a war zone) where the self becomes less important and the greater good of the unit (the hive) becomes the focus. This is how great feats of heroism, often leading to the hero’s own death, can be explained in great times of stress and violence. The tendency for absolute self preservation that is so dominant in the sedentary and individualistic American society falls away when the enemy is actually at the gate (not just proverbially at the gate as often suggested by campaigning politicians).

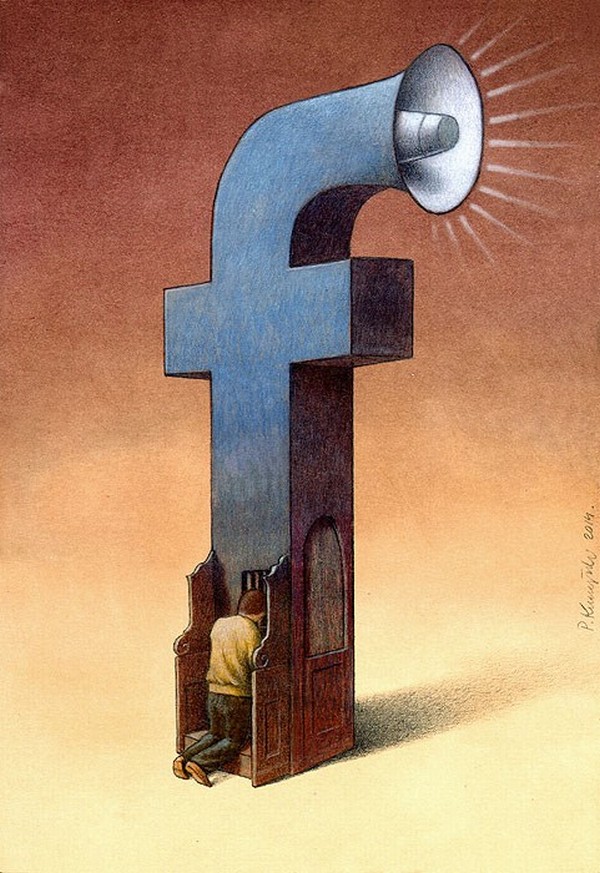

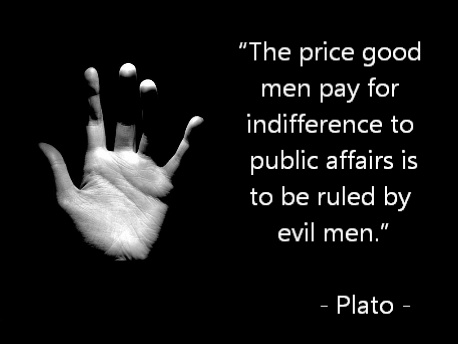

As I’m writing this, it seems to me a good litmus test for whether or not what a politician is trying to make you afraid of is an actual threat would be whether or not what the politician is saying makes you want to band together with your neighbors despite your differences, or become suspicious of your neighbors because of your differences. If the hive switch hypothesis holds true, then the real threats should make us want to join together, not tear apart. If the enemy the politician is describing are your neighbors, then the politician might just be trying to control you with irrational emotion. A theory to be explored another day.

So soldiers generally live in this tribal sense. They band together as brothers and sisters, lean on each other both physically and psychologically and fight for each other and for the families left back at the base. There are squabbles and competitiveness and not everyone gets along all the time. However, the differences that soldiers fight over are more communal and less demographically oriented. Fights are more likely to occur over who plays their music too loud in the barracks than who comes from an immigrant family or has a slightly different religious ideology. No one cares about that shit, because it’s not important. Soldiers have a strange way of speaking to each other, which is something that, even though I only lived in that culture for a minority 6 years of my life, returning to the way civilians speak to each other has proved to be far more difficult than it was to grow accustomed to the shit talking of the army.

In the army, if you were not accepted by the tribe (for whatever reason) then you were effectively shunned. People simply did not talk to the members who struggled to fit in. Whatever communication was required to accomplish tasks was handled very matter of factly. The bare minimum amount of conversation occurred during duty hours, and virtually no socializing with the misfit occurred during free time. If a member of the tribe was more or less accepted, but not fully trusted, then the speech patterns to those members could be described as courteous, but not very inviting. If you want to know whether or not a member of the tribe was not only accepted but fully trusted, count how many times that tribe member is called a fuckstick and his mother a dirty hooker. The more insults, the more trusted and accepted the tribe member is. This is what is referred to in the army as shit talking and if you weren’t doing it back, you were at risk of finding yourself in one of the outlier groups.

If I told a fellow soldier to nut-up, quit crying, un-bunch their panties and carry-on before anybody notices what a little bitch they’re being, then rest assured that language came from a place of love and genuine concern. It took a long time for me to accept that this is not an effective way to talk to people back in the civilian world. Although I accept it and I approach people from that place of acceptance, I still don’t thoroughly understand it and I have to say I don’t believe the civilian way of talking to one another is objectively better. As course and rude as the shit talking culture may seem, it gets results, fosters bonds between group members, propagates emotional antifragility, breaks down barriers and motivates people to overcome obstacles instead of allowing their obstacles to overcome them. To be sure, it’s not a nice way to approach people, but life ain’t nice and if a group is going to become a tribe then they better get used to things that aren’t nice.

So American veterans return from their tribal culture of service, often to find their country increasingly politically and socially divided. The chiefs seem perfectly content at cultivating an air of dread and fear (see above remarks about the enemy at the gate, so say the politicians), using emotional marketing tactics to split us into camps of us and them which is antithetical to the core of military and tribal life. The us vs. them mentality within military and tribal culture is more of a struggle with external forces; the enemy. Returning to America we find ourselves in a culture that seems to be focused solely on attacking itself, something that can be disheartening to the men and women who spent significant time and youth operating at great personal risk for the good of the country.

The American veteran often returns to society to find little to no real sense of community, especially in the urban culture where our population density seems to be inversely proportional to our knowledge of our neighbors. We live on top of one another, but rarely ever do we commune with one another. The rural American culture seems to be holding on to this sense of community a lot better than the urban life, but the rural life is itself under an existential crisis. The long trend of our population moving to the cities continues and the rural life is itself dying.

With the mass exodus to the cities also comes further loss of many key dynamics of tribal life. Namely having an intimate understanding and association with the day-to-day struggles necessary to keep society going. As we’ve moved into the cities, our positions in society have become increasingly specialized. Very few of us have a working knowledge of how food is grown, water is made potable, how lumber and other building materials come to be or how infrastructure keeps us going. The miners and loggers and farmers have become abstractions to us. In the liberal ideologies, these people are treated as simpletons and regressive laborers in environmentally archaic industries. In reality they are the communities, that is, the tribes who perform the functions that are the basic necessities of modern life. The city folk have just become too disconnected to understand this. This all comes together to form a modern existence that is simply difficult for veterans to reconcile. Often in the early days of America, when thousands of white Americans by hook or by crook found their way back to tribal life, attempts would be made to bring them back to cities and back to their modern way of life. Many times these people would reject it all and risk great harm to escape the city and return back to the tribe they had come to know and love.

The implication in Junger’s book is this is why some American war fighters miss the war, why Londoners following the blitz of WWII joked that they wouldn’t mind one night a week of bombings just to keep things interesting and why Israeli’s who live danger-close to their conflicts seem to escape many of the psychological aftermath that plague American military servicemen and women. Counter-intuitively, what we are lacking is a strong and communal country for veterans to come home to, we lack a culture prepared to help them feel useful, empowered and wanted in society. Veterans return to the country they left, only to find a nation of what my drill sergeant would call a bunch of goddamned individuals. If you had the tone and inflection of a drill sergeant’s voice in your head while reading that they way I had it in my head while writing it, you’d have no doubt that drill sergeant meant the word individual as a great insult.

I’ve never been very comfortable with people thanking me for my service. It’s something I’ve struggled with a lot since returning from the military. I know that my discomfort towards the gesture isn’t shared by all veterans, but I have recently and finally become aware that I’m not the only one. I ran into an essay on the internet a while back that let me know there are many other veterans out there who share my discomfort. I know the gesture is well-meaning, and I’m not mad that people feel motivated to make it, so I typically just say you’re welcome and leave it at that. I don’t stand up at ball games to be recognized and I don’t get free meals at participating restaurants on Veteran’s Day.

If I cut through the emotional response I have when someone thanks me for my service, which is mostly frustration, vulnerability and confusion, then I’d have to say a root cause of the emotion is that I’m not sure what people are thanking me for. I’m really not even sure if they know what they are thanking me for, which I think is one of the points of this book. The culture, the perception, the understanding and the fundamental dynamics between military, that is tribal life and the average American civilian experience is so far disconnected that the well-meaning gesture can seem to some veterans as something empty and obligatory. Well meaning civilians understand the veterans among them have done something, something deserving of gratitude, something they haven’t done…but they don’t seem to know what that something is. They don’t know what they are missing.

My emotions are not unique, which I was very happy to discover. I spent a long time feeling like there was something wrong with me, something ungrateful, for not feeling the gratitude that others were trying to express to me with their thanks. My emotions are also not standard for all veterans. I have many veteran friends who I’ve told about my feeling towards the phrases and gestures who don’t agree with me. Veterans aren’t as monolithic as some try to treat us. We come from a common forge of tribal culture, but we still retain a broad spectrum of diversity. That said, if you want some suggestions on alternative things to say to veterans, I would try asking them what their experience was like, how they feel it shaped them and what they have been doing since returning home. Junger suggests in this book that more needs to be done to make veterans feel useful and important in society, the way they were in their tribe. In my opinion, a lot could be done if more people made the effort to strengthen their communities and stop being assholes to their neighbors and their fellow Americans who have differences that are easy to focus on.

When I was a child I got into an after school fight with another boy in my class, I think I was in fifth or sixth grade at the time. We took the time to wait until school was well over, and the traffic of other kids and parents cleared up. After a few moments of the fight had passed (which seemed like forever), a man came out of an apartment across the street from the patch of grass we had chosen for our battle ground to stop the fight. I didn’t remember this until I started to write this post, but I think now I’ll never forget it. The man was tall, white, thin and his hair was buzzed short. He approached us shirtless from across the street, commanding us to stop fighting. He said that he had just gotten back from Iraq, the timeline matches up to the Gulf War, and that this is not what he wanted to come home to, this is not what he fought for. We broke up the fight and went our separate ways, the man walked frustrated and emotional back to his apartment. I didn’t really understand at the time why the man had taken such an issue with two kids fighting. In my childhood mind, if he was a soldier then he must have liked fighting. I think I understand what he meant now.

.

.